State-of-the-Art Language Models in 2020

Highlighting models for most common NLP tasks.

There are many tasks in Natural Language Processing (NLP), Language modeling, Machine translation, Natural language inference, Question answering, Sentiment analysis, Text classification, and many more… As different models tend to focus and excel in different areas, this article will highlight the state-of-the-art models for the most common NLP tasks.

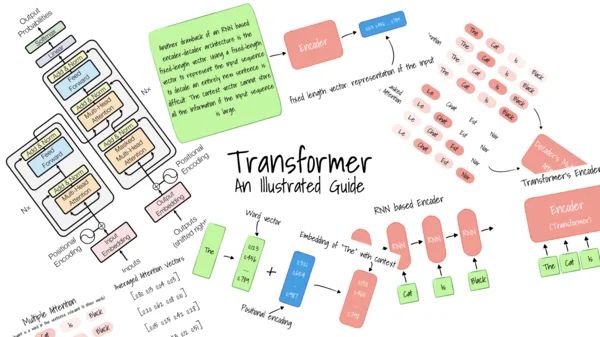

Transformer

Since the introduction of the Transformer, its variants have been applied to many, if not all, NLP tasks, achieving state-of-the-art performance. Sentiment analysis or text classification is no exception. Hence, an overview of the Transformer is provided in the section below, followed by different transformer-based models.

Before the Transformer was introduced, RNN models have been the state-of-the-art structure for sequence modeling and transduction problems. However, given the sequential nature of RNN computation, parallelization during training is mainly limited, resulting in less efficient training. The authors proposed an encoder-decoder structure, relying entirely on the attention mechanism, without the use of recurrent structures.

The encoder of the Transformer consists of 6-layers, each composed of a multi-head self-attention mechanism, followed by a feed-forward network. Before and after each sub-layer, a residual connection and an add & norm layer are added. The decoder has the same number of 6-layers. However, an encoder-decoder attention layer is inserted between self-attention and feed-forward layer. The attention mask is applied to hide tokens from subsequent positions.

The attention mechanism used is called Scaled Dot-Product Attention, which normalizes the logits by to prevent slow convergence due to a small gradient of softmax. Furthermore, the paper proposed Multi-Head Attention, such that the model can attend to information from different representation subspaces. The hidden states from all subspaces are then concatenated and projected, before the final classification layer.

In encoder self-attention layers, all the keys, values, and queries come from the previous layer, allowing the encoder to attend to all positions of the previous layer. The decoder self-attention, however, only attends to leading positions due to the attention mask. On the other hand, for encoder-decoder attention, queries are extracted from the previous decoder layer, whereas keys and values are from encoder hidden states. This allows the decoder to attend to all positions in the encoded sequence, which is crucial in sequence-to-sequence tasks.

In order to inject positional information, either relative or absolute, a positional encoding is added to input embeddings. In theory, it can be either learned or fixed; however, sinusoidal positional encoding is adopted for easier learning and extrapolation to longer sequences.

Bidirectional Encoder Representation Transformers

Traditional language models are unidirectional, where only words at previous time steps are visible during training. This is to ensure the predicted word does not indirectly “see itself.” However, in many sentence level or token level tasks, both forward and backward context is essential for optimal performance.

In 2018, a Bidirectional Encoder Representation Transformers (BERT) was introduced. It utilized masked language modeling (MLM) in a transformer structure to facilitate bidirectional representation training. Each input sequence starts with a special [CLS] token, the hidden state of which is used as a representation for classification tasks. For sentence pair input, a [SEP] token is added to indicate the boundary between individual sentences. The initial embedding of each token is summed with segment embedding and position embeddings as input to the Transformer.

The BERT model involves two pre-training tasks:

- Masked Language Model. During pre-training, 15% of all tokens are randomly selected as masked tokens for token prediction. However, as [MASK] is not present during fine-tuning, this leads to a mismatch between pre-training and fine-tuning. Therefore, among all selected tokens to be masked, only 80% are replaced with [MASK] token. 10% of the time the token will remain unchanged, and 10% of the time replaced by a random token. The author conducted ablation studies to show such a replacement ratio results in the best downstream performance. It is noteworthy that total replacement by [MASK] or total replacement by random token leads to suboptimal performance.

- Next Sentence Prediction. It is crucial to model the relationship between two sentences, especially for downstream tasks such as question answering or natural language inference. Therefore, the author proposed a Next Sentence Prediction task to classify whether a sentence is the trailing sentence of another. When choosing sentences 1 and 2 for sentence-pair input, 50% of the time, sentence 2 is an actual sentence that follows 1. The other 50% of the time, a random sentence is picked, serving as negative samples. This simple task has led to significant improvement for Question-Answering and Natural Language Inference tasks.

After pre-training, the model is fine-tuned on various downstream tasks by simply substituting appropriate input-output pairs. For token level tasks such as sequence tagging or question answering, hidden states of each token are fed to an output layer. On the other hand, the [CLS] hidden state is used for sentence-level tasks, such as entailment and sentiment analysis.

Researchers further explore BERT fine-tuning specifically for text classification, consisting of three parts:

- Use within-task or in-domain training data to further pre-train BERT

- Use multi-task learning to fine-tune (optional, if relevant tasks are available)

- fine-tune BERT for the target task.

The methods implemented include long text preprocessing, selection of layers, layer-specific learning rate tuning, forgetting, and few-shot learning.

XLNet

The aforementioned transformer-based models utilize autoencoding (AE) formulation rather than traditional autoregressive (AR) language modeling. As AE models do not factorize probability in a forward product as AR models, they can utilize context from both directions. Thus, closing the gap between language modeling and actual downstream tasks which often requires bidirectional information. However, as [MASK] token is absent in real data, this leads to a discrepancy between pre-train and fine-tuning. Furthermore, BERT assumes the predicted tokens are independent of each other, which is oversimplified.

In light of the pros and cons of both AR and AE language models, XLNet was proposed to leverage both their advantages while minimizing their limitations. Instead of using a fixed forward or backward factorization as in AR models, the authors proposed to maximize the likelihood of every possible permutation in factorization orders.

As the same set of parameters is used for all permutations, the model will always have access to the global context. Thus, it surpasses traditional AR models by extracting bidirectional information. Also, as there is no reconstruction from corrupted data, it avoids the issue of a pre-train fine-tunes discrepancy, as well as independence assumption. It is worth noticing that positional encodings are applied to preserve the original sequence order. The permutation is only achieved by using an attention mask on follow-up tokens in the factorization order.

However, the proposed formulation results in two contradictory requirements in transformer model:

- when predicting at time step t, the hidden representation h(t) should only contain positional but not content-wise information

- when predicting at time step >t, the h(t) includes both positional and content of token t

In order to resolve the issue, two separate streams, namely content and query representation, are used. Computationally, the query stream is trainable, and the content stream is initialized with corresponding word embeddings.

A large number of permutations cause slow training convergence of the model. Therefore, the author chose only to predict the last section of a factorization order. As such, speed and memory are saved as query representation need not be computed for the leading tokens.

So, can deep learning models like BERT ever understand language? This article on Neptune blog describes the three aspects that we should look for to understand NLP.